Postgraduate Essay: Can Popular Culture Be Heritage?

This English research essay was originally submitted in January 2017 for the postgraduate module ‘International Heritage: Politics, Policy & Practice’ at King’s College London. The present version has been revised and adapted for portfolio publication, with structural edits and minor refinements while preserving the original arguments and authorship.

The paper explores how Hong Kong’s neon signage—once part of everyday visual culture—can be reinterpreted through heritage discourses. It reflects my early academic interest in cultural memory, vernacular aesthetics, and contested narratives, which later informed my professional approach in branding and bilingual storytelling.

© Copyright held by the author. Academic citation and fair use are permitted with attribution. Reproduction or adaptation beyond academic use without permission is strictly prohibited.

Examining Hong Kong’s Neon:

Can Popular Culture Be Heritage?

Popular culture has a long history and has often been treated as something separate from more institutionalised forms of culture. Yet it remains largely absent from the official heritage landscape. Hong Kong, once famed for its dazzling neon-lit streets, offers a case worth examining. As this visual culture fades, it invites questions about what counts as heritage, who decides, and why some aspects of culture are preserved while others are allowed to disappear. This essay explores whether popular culture, exemplified by Hong Kong’s neon signs, can be reconsidered as cultural heritage. It draws on definitions of heritage and popular culture, presents a case study of neon signage, and engages with the politics of memory, commodification, and heritage-making in a postcolonial city.

Core Concepts

Heritage has long been defined by institutions such as the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) as encompassing not just landscapes and monuments, but also ongoing cultural practices and experiences (ICOMOS, 1999). Smith (2003) describes heritage as playing an important political, social and educational role. It is both material and immaterial—a process of selection and recognition that reflects values and identities. In this sense, heritage is less about what survives from the past, and more about how the past is used in the present (Lowenthal, 1997).

Importantly, there is no universal consensus on what counts as heritage (Xie, 2016). Graham, Ashworth and Tunbridge (2000) argue that meaning, not artefact, should be central to heritage definitions. This aligns with constructivist interpretations of heritage, which see it as a means of transforming memories and material artefacts into cultural or political resources (Ascensión, 2008). For UNESCO (2003), cultural heritage includes not just physical objects but also the knowledge, practices and expressions recognised by communities themselves.

Notions of Popular Culture

Popular culture, meanwhile, is a notoriously slippery concept. Storey (1997) outlines six competing definitions, from ‘widely favoured’ to ‘mass culture’ to ‘a terrain of ideological struggle’. Hall (1981) emphasises the political nature of popular culture, framing it as a site of contestation and resistance. In a postmodern context, the line between high and low culture has further blurred, and popular culture often intersects with commercialism and nostalgia.

Hong Kong’s neon signs, as this essay argues, fit within several of these definitions. They are widely consumed, visually dominant, tied to commerce, and deeply symbolic. They were created and shaped by ordinary people, not elite cultural producers, and they have become the subject of both adoration and controversy. The rest of this essay explores how these signs function not only as popular culture but also as potential heritage.

Case Study of Hong Kong’s Neon Signs

Neon signage emerged in Hong Kong in the early 20th century and flourished after the Second World War. At its peak in the 1970s, neon signs could span entire building facades, including a Guinness World Record-breaking installation in Kowloon (West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, 2014b). By 2013, an estimated 120,000 outdoor signs populated the city (Chan, 2013). Yet from the 1990s onwards, many of these were dismantled, replaced by LED displays and plastic billboards. Officially, the reason was safety; in practice, the removals signalled a broader reshaping of Hong Kong’s urban character (Cheung, 2015)

Still, neon signage has refused to vanish entirely. Though largely gone from street corners, it survives in restaurants, boutiques, and as interior design. Art projects and museum initiatives—most notably the 2014 M+ project NEONSIGNS.HK—have attempted to preserve, document and reinterpret these glowing relics (West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, 2014a).

Signs of an Era

Neon lights in Hong Kong differ markedly from those in other cities. In places like Las Vegas or Tokyo, neon often signifies entertainment. In Hong Kong, it once signified everything—pawn shops, restaurants, pharmacies, supermarkets. Their presence in dense urban spaces, jutting out into roads, competing for attention, became a defining feature of the city’s streetscape. Design strategies varied by industry: restaurants illustrated menu items, nightclubs mimicked Western fantasies, and pawn shops stylised traditional characters with cultural flair (Lam and Kwok, 2014; Kwok in Lam, 2017).

This visual language merged Chinese calligraphy with Western typographic influences, creating a hybrid aesthetic unique to post-war Hong Kong (Sprengnagel, 1997; Tam, 2014). These signs were not only advertising tools but also semiotic devices that shaped the collective urban experience. They offered more than just light. Symbolism. Memory. Meaning. Stuff that doesn’t show up in a building code.

Neon Signs as Popular Culture

If popular culture is the culture of the people, Hong Kong’s neon signs qualify. They were built by local craftsmen, funded by small and large businesses, consumed daily by the public, and deeply woven into everyday life. Their presence was not curated from above but emerged from below, shaped by market needs and aesthetic experimentation. They reflect a localised class dynamic as well: signage was a battleground for visibility, with larger businesses able to outshine smaller ones. This also became a struggle between creative and regulatory classes—between those who wanted to decorate the city and those who wanted to sanitise it.

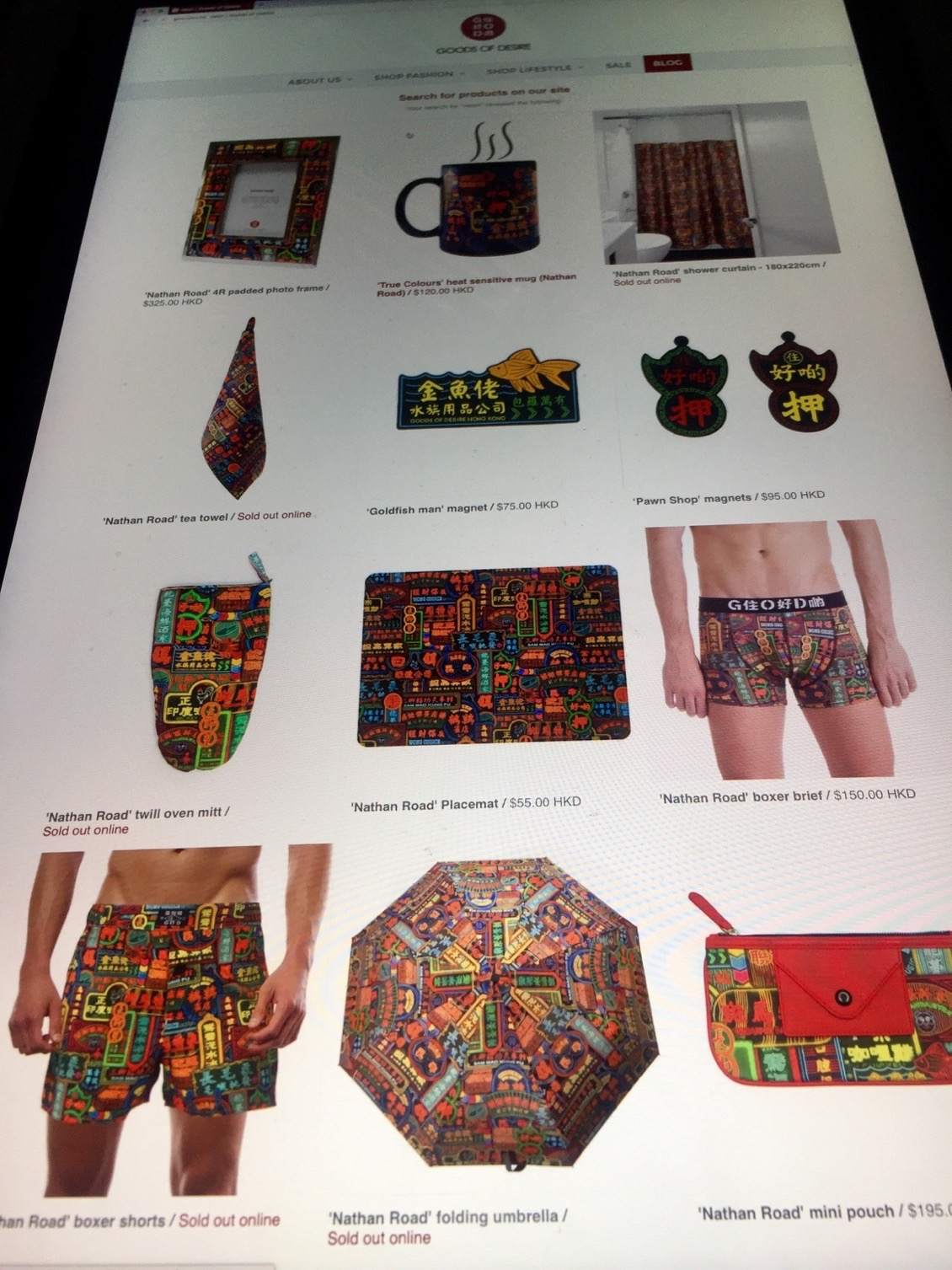

Neon signs have also deeply inspired cultural production. Filmmakers like Wong Kar-Wai and Ridley Scott have drawn on Hong Kong’s neon streets as visual metaphors. So have anime creators (e.g., Ghost in the Shell) and musicians from Tat Ming Pair to Blur. Commercial brands like Goods of Desire have reproduced neon motifs on T-shirts, tote bags and homeware (Chibber, 2009). This reappropriation shows how neon signage, once dismissed as clutter, has become a visual shorthand for retro urban chic.

Commodification and Nostalgia

The popularity of neon imagery today is closely linked to commodified nostalgia. As Hillenbrand (2010) argues, East Asian nostalgia often involves a ‘picture-perfect’ rendering of the past—a fantasy space divorced from historical discomforts. In Hong Kong, neon has become retro-cool, used to style interiors and products, not as living infrastructure but as vintage décor. In this context, nostalgia acts not only as an emotional response, but also—sometimes awkwardly—as a commercial strategy (Hillenbrand, 2010; Rinaldi, 2012), depending on how it’s used.

This raises questions about authenticity and intention. Is neon being preserved, or repackaged? And who benefits from this stylised memory? The same government that allowed neon’s dismantling now features its imagery in tourism campaigns. Trendy businesses co-opt its aura for ambience, while former neon artisans struggle to find work. The neon sign, then, is not just a nostalgic object—it’s a case study in how culture can be monetised, repurposed and stripped of context. It’s hard to say whether this kind of design nostalgia actually preserves the cultural meaning of neon—or just flattens it into a mood board.

Memory Politics and Heritage from Below

The removal of neon signage also exemplifies contested memory in urban environments. Official narratives framed the removals as technical and necessary, yet many Hongkongers interpreted them as symbolic erasures. This echoes what Ku (2012) calls the ‘counter-discourse of people’s space,’ where ordinary citizens challenge top-down definitions of value and meaning. Neon signs, long dismissed by regulators, are now seen by the public as carriers of cultural memory.

Grassroots groups like Street Sign HK and Tetra Neon Exchange have responded by salvaging signs, archiving photographs and interviewing former signmakers (HKFP, 2023). These efforts reflect a democratisation of heritage, where preservation is no longer the sole domain of state institutions. Instead, it becomes participatory, affective, and personal. Projects like NEONSIGNS.HK showed how museums, too, can embrace this model—inviting public contributions, organising workshops and digitally mapping remaining signs (M+, 2014).

Such actions reflect a shift from authorised heritage discourse to heritage from below (Smith, 2006). They reveal that cultural value is not inherent, but negotiated—often fiercely. In this negotiation, neon perhaps becomes a vessel of identity here—one that, it could be said, reflects a Hong Kong increasingly uneasy about redevelopment and political change.

Neon as Symbol and Urban Myth

The symbolic power of neon extends beyond aesthetics. Neon is mythologised as part of Hong Kong’s urban identity—an icon of its mid-century modernity, multiculturalism and economic ascent. It conjures a time when the city projected confidence and colour, when streets buzzed with possibility. Today, that glow is dimming, both literally and figuratively.

In a postcolonial context, this myth-making becomes politically charged. As Hong Kong negotiates its relationship with China and its own fractured identity, the visual memory of neon becomes a site of cultural resistance. It speaks to a longing not only for light, but for continuity, autonomy, and visibility. As one commentator noted, removing the sign is not just about taking down a structure—it’s ‘removing the soul’ of a place (Leung, 2023)

Conclusion

Hong Kong’s neon signs illustrate how popular culture can intersect with heritage. They were built by ordinary people, consumed in daily life, and eventually reimagined through nostalgia and design. Their fate reveals the cultural politics of memory, the commodification of the past, and the evolving role of the public in shaping what is remembered. While neon signs may not fit traditional models of heritage, they clearly carry emotional, symbolic and historical weight. As definitions of heritage expand, neon should not be excluded simply because it is commercial or popular. In fact, it is precisely these qualities that make it meaningful.

In the glow of neon, we see the layers of a city—its dreams, tensions, identities and myths. Whether hanging above a noodle shop or preserved in a museum crate, these signs remind us that heritage is not only about what stands tall, but what flickers, fades, and refuses to be forgotten.

Ascensión, H.M., 2008. Conservation and restoration in built heritage: a Western European perspective. In: J. Graham and P. Howard, eds. The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.245–266.

Bernard, A., 2006. Lifted from Rinaldi (2012).

Berger, T., 2014. Off-on: neon in art. [online] Available at: http://www.neonsigns.hk/neon-i... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Cass, G. and Jahrig, S., 1998. Heritage tourism: Montana’s hottest travel trend. Montana Business Quarterly, 36, pp.8–18.

Chan, Y., 2013. Signs of the times. HK Magazine. [online] Available at: http://www.scmp.com/magazines/... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Cheung, Y., 2015. Hong Kong's farewell to thousands of neon signs. The Creators Project. [online] Available at: http://thecreatorsproject.vice... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Chibber, K., 2009. Store review: G.O.D. in Hong Kong. The New York Times. [online] Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Chow, C. and Lai, B., 2020. Collecting Neon Signs from Hong Kong’s Streets. M+ Magazine. [online] Available at: https://www.mplus.org.hk/en/ma... [Accessed 10 Jul. 2025].

Cohen, E. and Cohen, S.A., 2012. Current sociological theories and issues in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(4), pp.2177–2202.

De Groot, J., 2009. Consuming History: Historians and Heritage in Contemporary Popular Culture. Abingdon: Routledge.

De Waal-Montgomery, M. and Gan, N., 2014. Neon signs: a shining example of Hong Kong's heritage. South China Morning Post. [online] Available at: http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-... [Accessed 31 Dec. 2016].

Dobson, N., 2009. Ghost in the Shell. In: The A to Z of Animation and Cartoons. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, p.87.

Feilden, B.M. and Jokilehto, J., 1993. Evaluation for conservation. In: Management Guidelines for World Cultural Heritage Sites. Translated by B. Abazi and J.L. Andreassen. Prishtina: Cultural Heritage without Borders, pp.13–26.

Goods of Desire, 2017a. Nathan Road collection. [online] Available at: https://god.com.hk/collections... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Goods of Desire, 2017b. Neon. [online] Available at: https://god.com.hk/search?type... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Graham, B., Ashworth, G.J. and Tunbridge, J.E., 2000. Heritage, power and identity. In: A Geography of Heritage. London: Routledge, pp.29–54.

Gwinn, I., 2009. Review of Consuming History. Reviews in History, 825. [online] London: Institute of Historical Research.

Hall, S., 1981. Notes on deconstructing the popular. In: R. Samuel, ed. People’s History and Socialist Theory. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.227–239.

Hillenbrand, M., 2010. Nostalgia, place, and making peace with modernity in East Asia. Postcolonial Studies, 13(4), pp.383–401.

ICOMOS International Committee on Cultural Tourism, 1999. International Cultural Tourism Charter. Mexico: ICOMOS.

James, M., 2005. Neon signs Kowloon. [image online] Available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Jiang, X., 2009. Chinese characters on architecture. In: The Beauty of Chinese Calligraphy. Taipei: Yuan-Liou Publishing, pp.228–241.

Ku, A., 2012. Remaking Places and Fashioning an Opposition Discourse: Struggle over the Star Ferry Pier and the Queen’s Pier in Hong Kong. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 30(1), pp.5–22.

Lam, H.Y., 2017. Local aesthetics: gradually disappearing neon lights. HK01. [online] Available at: https://www.hk01.com/article/6... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Lam, P.L. and Kwok, L.O., 2014. Neon lights continue to shine. iMoney. [online] Available at: http://lifestyle.etnet.com.hk/... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Leung, H., 2023. Hong Kong’s fading neon heritage shines a spotlight on the craft. Hong Kong Free Press. [online] Available at: https://hongkongfp.com/2023/04... [Accessed 5 Jul. 2025].

Li, Z., 2014. Can Hong Kong save its neon signs? CNN. [online] Available at: http://edition.cnn.com/2014/03... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Lowenthal, D., 1997. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ribbat, C., 2014. Tomorrow’s neon: a history. [online] Available at: http://www.neonsigns.hk/neon-i... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Rinaldi, T.E., 2012. Reading neon. In: New York Neon. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, pp.7–21.

Smith, M.K., 2003. Globalisation of heritage tourism. In: Issues in Cultural Tourism Studies. London: Routledge, pp.99–116.

Sprengnagel, D.J., 1997. Hong Kong. In: Neon World. New York: HarperCollins Design International, pp.112–125.

Storey, J., 1994. Introduction. In: Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: A Reader. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.xv–xix.

Storey, J., 1997. What is popular culture?. In: Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.1–15.

Tam, K., 2014. The Architecture of Communication. NEONSIGNS.HK. [online] Available at: http://www.neonsigns.hk/neon-t... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

UNESCO, 2003. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO.

West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, 2014a. Neon map. [online] Available at: http://www.neonsigns.hk/?lang=... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, 2014b. Neon timeline. [online] Available at: http://www.neonsigns.hk/neon-t... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, 2014c. The making of neon signs. [online] Available at: http://www.neonsigns.hk/video/... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, 2014d. Tours | workshops | talk. [online] Available at: http://www.neonsigns.hk/tours-... [Accessed 15 Jan. 2017].

Wheale, N., 1995. Postmodernism: from elite to mass culture?. In: The Postmodern Arts: An Introductory Reader. London: Routledge, pp.33–56.

Xie, P.F., 2015. Approaches to industrial heritage tourism. In: Industrial Heritage Tourism. Bristol: Channel View Publications, pp.16–56.

Post a comment